Northern Pole of Inaccessibility – Arctic Pole

The Northern Pole of Inaccessibility, in the Arctic, is one of the original Eight Poles.

The Northern Pole of Inaccessibility is defined as the point in the Arctic Ocean that is the farthest from any coastline. Unlike the continental poles of inaccessibility, this one does not rest on land but lies amid the drifting pack ice of the central Arctic Basin, which makes it difficult to get to.

- Latitude: 85°48’N

- Longitude: 176°09’E

- Distance from land: 1008 km/626 miles

The closest coasts are those of Henrietta Island in the De Long group, Cape Arctic on Severnaya Zemlya, and Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic. The Arctic Pole is around 662 kilometres (411 miles) south of the Geographic North Pole.

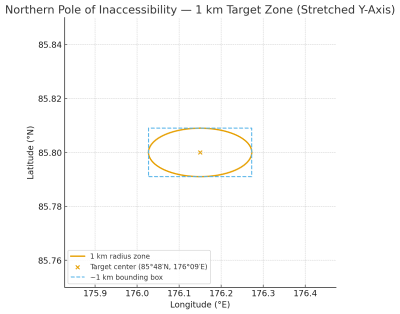

Because the sea ice is always in motion, the pole itself is never a permanent or fixed spot on the ice surface which makes the coordinates particularly difficult to visit. However, there is an error margin given in the definitive calculations of ±1 km. In other words, if you can navigate to 85°48′N, 176°09′E ± (0°00′32″ lat, 0°07′41″ lon), you’re within the 1 km error margin of the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility.

[Note: You’ll see some sites give the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility coordinates as 85°48′N, 176°09′W; with the letter W for ‘West’ being a common transcription error. The peer-reviewed Polar Record by Rees et al. specifically states E for ‘East’.]

History of the Arctic Pole of Inaccessibility

The Northern PIA was originally thought to be at 84°3′N 174°51′W. Nobody knows for sure where these coordinates came from. Perhaps they were calculated by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, or perhaps by the aviator Sir Hubert Wilkins who first attempted to fly across the Arctic in 1927.

Reaching this location has proven far more difficult than simply walking to a set of coordinates. The constantly shifting ice, extreme cold, and sheer remoteness mean that very few expeditions have ever attempted to stand at this pole.

Sir Wally Herbert came close to being the first to this pole in 1968 by dogsled, bt failed due to the ice pack movements. Then a Russian expedition including Dmitry Shparo said they skied thruogh the pole one arctic night, but offered no other proof.

In 2005, explorer Jim McNeill asked scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and the Scott Polar Research Institute to update the position of the pole using modern GPS and satellite data. The revised location (coordinates above) was later published in Polar Record in 2013 by Gareth Rees (Scott Polar Research Institute), Robert Headland (SPRI), Ted Scambos (NSIDC), and Terry Haran (NSIDC).

McNeill set out the following year (2006) to be the first to reach it while also gathering sea-ice data for NASA, but the expedition was forced to turn back. He tried again in 2010 with his Ice Warrior team, only to be beaten once more by the poor state of the drifting ice.

Other explorers, such as the Norwegian Børge Ousland, have also approached the area, but the shifting ice and logistical challenges have ensured that the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility remains one of the least-visited and most elusive points on Earth.

In 2020 Frederik Paulsen became the first person to record a visit to the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility in his own quest to visit eight poles (these are a different eight poles from my own quest. His were the Geographic Pole, Geomagnetic Pole, Magnetic Pole and Poles of inaccessibility for the Northern and Southern hemispheres)

Finally, on the On 12 September 2024, the French Icebreaker ship, Le Commandant Charcot, became the first ship to definitively reach the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility.

Getting to the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility

My first attempt at the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility was in April 2019. It was chosen as my first pole because, at that time, it had not been officially visited. Sadly it was to stay that way.

The ‘standard’ way of geting onto the ice and to make an attempt at the regular North Pole was to fly from Svlabard to a landing strip prepared on the ice called Barneo. Each year Barneo would be in a different location, requiring a 2 km section of ice that hadn’t melted for at least two years.

The runway would be prepared by Russian contractors who dropped in with their machinery by parachute. Unfortunately, the aircraft used for reaching the ice were Ukrainian Antonov An-74 aircraft. Zelensky had just been elected and tensions between the two countries were escalating. The Russians raised their flag at Barneo and refused Ukrainian aircraft into ‘their’ airspace.

As a result, we spent nearly two weeks in Longyearbyen fully prepped up to go to the ice and pull our pulks to the Pole. All dressed-up and nowhere to go.

1309km from the North Pole

Covid 19 soon followed and then the Ukraine-Russia war, so that traditional route was all but abandoned.

In the meantime, I visited Point Nemo on the Hanse Explorer and discussed with the captain the possibility of icebreakers (which were getting ever-stronger) cutting through the sea-ice (which is getting weaker each year through climate change) all the way to the Northern PIA.

Imagine my surprise when I was then sent an image of the Commandant Charcot crew celebrating being the first to record a visit to the pole!

Anyway, it might not be as adventurous as some of my other Pole of Inaccessibility expeditions, but beggars can’t be choosers, so I discussed the possibility of a re-visit with Ponant, the ship’s owners, and they were happy to accommodate the little side-trip again from their ‘two poles’ cruise (geographic and magnetic poles).

Second Attempt at the Arctic Pole

On 5th September 2025, I flew to Svalbard again, this time via Paris. I’d hoped for a bit of time in town to revisit some of the haunts in which we’d spent so much time, but the Captain was keen to depart. So, we all boarded the Commandant Charcot and departed for a few days looking round Svalbard itself.

We visited Ny-Ålesund, a research settlement on the island of Spitsbergen from where many early attempts to fly to the regular North Pole departed. There were also many visits to different parts of tidewater glaciers termini to witness calving such as Waggonwaybreen and Monacobreen. We saw humpback whales, walrus’ colonies and even an artic fox that came trotting within about 20m of us on one hike.

Then it was time to head North into the ice. By 11th September we entered the first stages of thin layered sea ice which forms when the surface of the ocean cools to its freezing point, typically around -1.8°C (28.8°F) for seawater. The first thin, elastic layer is known as “Nilas” which appears dark and almost translucent.

Over the next few days the ice would gradually thicken. None of it a problem for the Commandant Charcot which can easily cope with ice that’s two metres thick. Apparently three metres is ‘doable’ but might cause a problem!

my hunting ground?

On the 12th the ice was thick enough to be a hunting haven for Polar Bears. Plenty of open water where seals(food) might appear but thick enough to hold their weight. Sure enough, we were blessed with seeing three of these magnificent creatures. A lone female who took interest in the boat and then another female with her young (but fairly well-grown) cub.

On Saturday 13th September we reached 90° North – the terrestrial Geographic North Pole. The temperature here varies between 0°C and -43°C. We were there on one of the balmier days at around -5°C. Pretty close to the North Pole the ship ‘parked’ and we got out on to the ice.

Three days later we arrived at the magnetic North Pole, or at least an interpolation of where that pole would be on 16th September. Certainly, our compasses went a bit haywire, but in the absence of a declination compass we couldn’t tell how accurate that position was. Anyway, the position reached was:

- Latitude: 285°37’N

- Longitude: 136°54’E

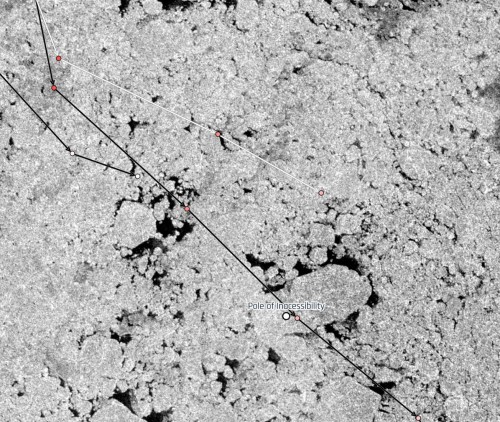

Next up was the most exciting for me, but less so for my fellow travellers. The Northern Pole of inaccessibility. On the night of September 17th, we arrived within 1km of the pole’s coordinates. Given that the error margin is a 1km circle, technically that qualified as ‘reaching the pole’.

Not satisfied with that, Captain Patrick Marchesseau ‘parked’ the boat on some multi-year ice for the night. According to their calculations, flow data, currents, satellite images and other technical factors, they hoped to wake up the next morning at the exact pole. Of course, that didn’t happen, we woke up 7.5km from the pole! Anyway, we took the opportunity to walk around the firm ice, whilst the on-board scientists took their measurements.

Later in the day (18th September) at around 18:00 we sailed to almost exactly the accepted coordinates of the Arctic Pole of Inaccessibility.

Date Visited: 18th September, 2025

Weather: -7° Celsius/19° Fahrenheit.

Coordinates Achieved: 85°48.00’N, 176°09.05’E

Distance from Pole: 7 metres

Looking down at the pole from an ice breaker it occurred to me that our original expedition would have been doomed to failure. There are far more pressure ridges than I’d reckoned on. What is more there is also much more open water than I’d thought. Navigating those ridges, the open water and trying to better a modern ship’s capabilities of calculating currents would have been nigh on impossible.